Cooperative Infant Care and Human Evolution

No mother does it alone. Well, no human mother.

An important difference between humans and other apes is that women simply can not raise their young without help. As infants, we have to grow bigger brains and yet our mothers wean us at younger ages. Fossils of early human ancestors show that relative brain size was beginning to get larger by about 1.8 million years ago, suggesting that the at this point mothers likely needed help. Who was helping?

"Mother and Child" by John Henry Twatchman, 1893

In the 1960s, many scholars proposed “Man the Hunter.” Males, by providing nutrient rich meat to their mates, were the obvious critical factor in shaping human evolution (Lee and DeVore 1969). The assumed importance of the human male-female bond for infant rearing and lifetime reproductive success inspired decades of social and evolutionary psychology research on human mating behavior. Picking mates, attracting mates, and guarding mates was of paramount importance for humans because our very fitness depended on the quality of the mate, the co-parent.

Mammal March Madness 2014

(also does anyone know who did this artwork?)

But are monogamously pair-bonded hominin parents sufficient?

Probably not. Across human cultures, infant and child care is due to cooperation among many individuals playing a diversity of care-taking roles (Hrdy 2009, Kramer and Ellison 2010). These wider social networks of grandparents, step-parents, aunts, uncles, older siblings, friends, and others contribute to feeding, protecting and teaching young humans. That’s today, but what happened in our evolutionary history? Such cooperation may have emerged from monogamous pair-bonds, male cooperative networks, or possibly female cooperative networks.

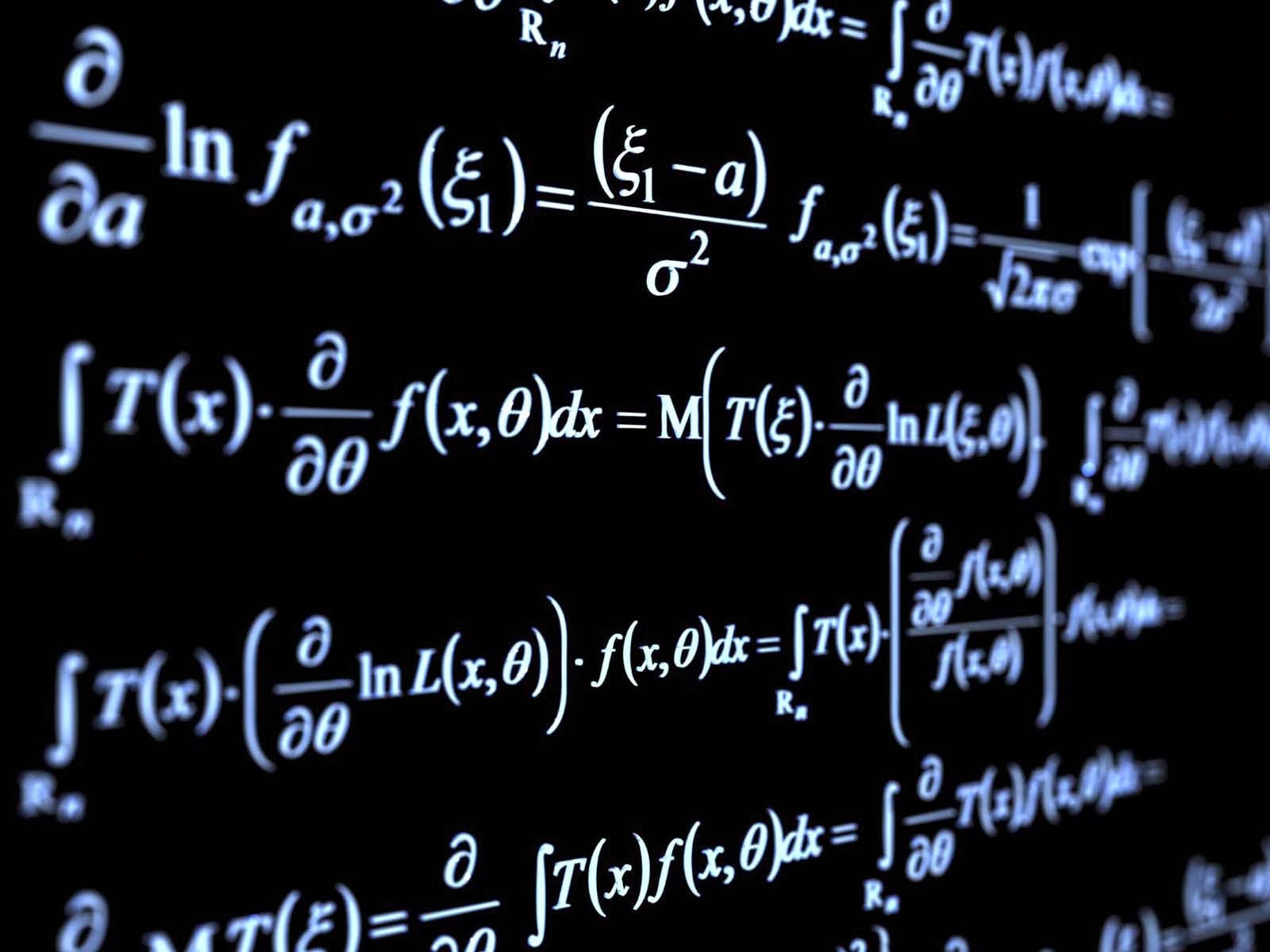

Unfortunately, behavior doesn’t exactly fossilize. As such theoretical models of evolutionary dynamics can shed light on what possibly happened nearly two million years ago. My colleagues, evolutionary theorists Adrian Bell of the University of Utah and Lesley Newson of UC Davis, and I developed a mathematical model to explore how cooperation may have been favored and specifically who was cooperating (Bell et al. 2013). We know that natural selection would favor the set of behaviors-- or “strategy”-- that was likely to have left the most descendants. Of course, which strategy is best depends on the individuals that are interacting and the habitat in which these interactions occur. We estimated the likely benefits and risks of different strategies based on empirical data in the literature from humans and non-human primates.

Mathematical models can combine the costs, risks, and benefits of each strategy to determine whether males (aka Man the Hunter) or some other source of help allowed females to support the faster birth rate of larger-brained babies. Many key concerns were built into the math: benefits of group vs. solo hunting among males, whether or not the male was actually the father or a cuckold, female cheaters that took help but didn’t give back, and whether there was relatedness among males or among females.

Wikimedia Commons, by Wallpopper

Sidebar: There are millions of potential REAL WORLD individuals from whom we could collect actual data. Why the heck do we need mathematical models? Why do we even have entire journals dedicated to theoretical modeling of evolutionary processes? Because living, breathing, behaviorally acting individuals out walking around have adaptations that have already gone through selective bottlenecks- so mutant and novel phenotypes are exceedingly rare. In the course of typical behavioral data collection, such rare variants are necessarily under-represented in datasets.

For example when I was doing my dissertation research, there was one monkey mom that habitually tandem nursed her newborn and yearling. Her body weight dropped considerably, even though she was the alpha female of the social group. Her adult daughters stopped affiliating with one another and increased fighting with each other, possibly because the alpha in her relatively depleted state was less motivated to intervene. And then the beta matriline cooperatively kicked the alpha matriline’s collective booty and became the new alpha matriline. Although this story is epic cocktail party fodder, I can’t make any arguments about tandem nursing in monkeys because N=1. Theoretical modeling allows you to explore the entire landscape of behavioral phenotypes, shuffled loose the empirical coil of vast numbers of typical variants with the occasional rare extreme "winner" and extreme "loser" variants. End Sidebar

Our analyses triangulated on the scope for male helping vs. female helping, in effect asking how much does it take for mother-mother cooperation to be favored by natural selection. The answer is: not much. Given the assumptions about reproductive physiology, the scope for cooperative caregiving among mothers is favored to a much greater extent than is monogamous pair-bonds between a mother and “Man the Hunter.” Mothers do not even have to be related for cooperation among females to be favored (although kinship can favor the evolution of cooperation faster, as expected). In the long run the benefits to cooperative mothering far out-weigh the costs associated with “cheating mothers” or extra difficulties of short-term care-taking of another mother’s infant at the same time as caring for one's own. While we are by no means alone in considering the role of women's social networks in human evolution, this is the first theoretical model of the evolutionary dynamics that may have been operating.

First author Adrian provides some further key points: “To be clear, we are not claiming that help from males made no contribution to our evolution, but we think it almost certainly did not happen with males and females being pair-bonded and the male concentrating on helping “his” mate and her children. Our early ancestors were more likely engaged in broad cooperative networks between females and also males." Lesley further points out "in all human groups living today, people coordinate their work and pool their resources. Humans love, marry, and bond, but keep in mind, in many traditional societies the creating the “match” for marriage involved the couple and their families. In part, these social mechanisms ensure that mothers have broad support now and into the future.”

Adrian Bell and kiddo.

For those who have recently or will soon gather with friends and family over shared food and festivities- after all numerous religions celebrate holidays in November and December- arguably nothing more emphatically demonstrates being human than our incredible capacity for cooperation. Happy holidays to all.

______________________

Citations:

Bell AV, Hinde K, Newson L (2013) Who Was Helping? The Scope for Female Cooperative Breeding inEarly Homo. PLoS ONE 8(12): e83667.

Hrdy, S. B. (2009). Mothers and others. Belknap Press.

Kramer, K. L., & Ellison, P. T. (2010). Pooled energy budgets: Resituating human energy‐allocation trade‐offs. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 19(4), 136-147.

Lee, R. B., & DeVore, I. (Eds.). (1969). Man the hunter. Transaction Publishers.

Comments

Post a Comment